Last Friday (20th June) I attended a conference on ‘Objects and Remembering’ at the University of Manchester. The event brought together people working on the relationship between objects and memory from a number of different perspectives – archaeology, history, museum and heritage studies, forensics and geology. It was a highly stimulating day, full of lively discussion and a realisation that many of us were headed in the same direction, even if we were taking very diverse routes in our attempts to get there. What was our shared goal? To better understand both the way in which objects are implicated in memory-making, and the consequences of memory for the meaning-making associated with objects.

Several themes emerged over the course of the day that I have continued to reflect upon, especially in terms of their relevance to the study of votive practice: authenticity (of objects, experience, and memory); the creation and expression of different types of memory objects (scientific data produced by the study of fossils being a different, but no less important, type of meaningful ‘memory’ from that associated with the emotional memories of collecting the geological specimen); the intentional absence of objects from a particular setting or context as a strategic form of remembrance (empty spaces at Knossos); the potential of objects for engaging different groups with their own past, and that of others, via multidirectional memory or postmemory (displaced or migrant populations and community archaeology projects); the communication and/or creation of collective memory via personal objects (objects as material primes in reminiscence sessions); contested meanings and curated objects, past and present (an heirloom bracelet at Silbury Hill). Key words repeated throughout the day were ‘emotion’, ‘commemoration’, ‘senses’, and ‘materiality’.

Some of these ideas seem more immediately relevant to votives than others. Perhaps ironically, if unsurprisingly, however, the clearest conclusion of the day – for me at least – was that objects are never objective, nor are our interactions with them. In terms of votives this seems pertinent since we know that these objects combined memory and meaning and were designed to be used in certain ways and in specific contexts.

What might the implications of these themes be for those of us interested in studying votives? Issues of authenticity were something that not only struck me as crucial, but which resonated quite strikingly across the papers presented on the day. What makes something – an object, a memory, an experience, a sensory perception, the exhibition or interpretation of objects – authentic? Why does it matter and how might contesting authenticity change the way that objects are given meaning? In terms of votives, of all types, in what ways do these offerings authenticate the experience of dedication? To what extent, moreover, are they expected to accurately represent or reflect the wider vow or religious process in which they are implicated and is it possible for this to be contested? Do they somehow make the reality of that religious act ‘authentic’ and therefore meaningful? How does the form of am ex-voto communicate to others the authenticity of the process and what happens if subsequent interaction with it actually serves to complicate that authenticity?

What might the implications of these themes be for those of us interested in studying votives? Issues of authenticity were something that not only struck me as crucial, but which resonated quite strikingly across the papers presented on the day. What makes something – an object, a memory, an experience, a sensory perception, the exhibition or interpretation of objects – authentic? Why does it matter and how might contesting authenticity change the way that objects are given meaning? In terms of votives, of all types, in what ways do these offerings authenticate the experience of dedication? To what extent, moreover, are they expected to accurately represent or reflect the wider vow or religious process in which they are implicated and is it possible for this to be contested? Do they somehow make the reality of that religious act ‘authentic’ and therefore meaningful? How does the form of am ex-voto communicate to others the authenticity of the process and what happens if subsequent interaction with it actually serves to complicate that authenticity?

Although I did not initially think of it in these terms, my own paper at the conference dealt with similar questions. I spoke about the ambiguity of Italic terracotta swaddled babies and the fact that they appear to sit uncomfortably between two realms, as the materiality of these objects and the actions associated with their dedication, act together to confuse or muddle the senses. Is the object a baby or a representation of a baby? How might this uncertain authenticity lend particular meaning to the dedication of such an ex-voto? Can blurring the lines ever be intentional?

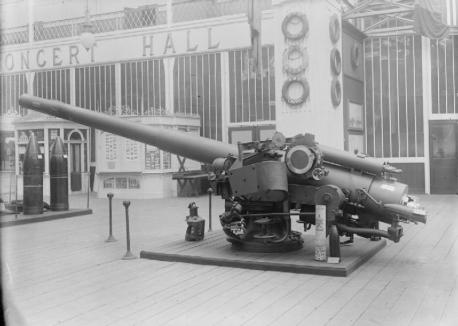

We might compare this with other contexts explored at the conference in which ‘authenticity’ takes on different types of meaning: the use of original 1950s objects in handling sessions with people with and without dementia where authenticity means using original items, associated with real life past experiences, to aid the recall of deeply embodied memories; the decision to use replicas of certain objects in Elizabeth Gaskell’s House (Manchester) to create a more ‘authentic’ and meaningful experience; the authenticity of the shared memories constructed upon the excavation of a mass grave of the Spanish Civil War in a small community. Authenticity might also be open to change: for the first visitors to the Imperial War Museum, who had themselves been involved directly in the events being commemorated, it was important for them to interact with the actual gun that 16-year-old Jack Cornwell was working on when he died, and important that they could name the individual whose blood had been spattered across a ship’s log. For these veterans, argued Alys Cundy, the cenotaph designed by Lutyens to commemorate these events, was inauthentic. However, for later generations it is these initially inauthentic objects that have become the focus of collective memories and commemorative activities; they have accrued their own authenticity. The authenticity of the authentic might therefore be a matter for debate and negotiation, in both the past and the present and indeed between participants in the same activities.

We might compare this with other contexts explored at the conference in which ‘authenticity’ takes on different types of meaning: the use of original 1950s objects in handling sessions with people with and without dementia where authenticity means using original items, associated with real life past experiences, to aid the recall of deeply embodied memories; the decision to use replicas of certain objects in Elizabeth Gaskell’s House (Manchester) to create a more ‘authentic’ and meaningful experience; the authenticity of the shared memories constructed upon the excavation of a mass grave of the Spanish Civil War in a small community. Authenticity might also be open to change: for the first visitors to the Imperial War Museum, who had themselves been involved directly in the events being commemorated, it was important for them to interact with the actual gun that 16-year-old Jack Cornwell was working on when he died, and important that they could name the individual whose blood had been spattered across a ship’s log. For these veterans, argued Alys Cundy, the cenotaph designed by Lutyens to commemorate these events, was inauthentic. However, for later generations it is these initially inauthentic objects that have become the focus of collective memories and commemorative activities; they have accrued their own authenticity. The authenticity of the authentic might therefore be a matter for debate and negotiation, in both the past and the present and indeed between participants in the same activities.

Memory, of course, is especially pertinent to the study or understanding of ex-votos. A votive, after all, was intended primarily to serve as a mnemonic device, a reminder to both mortal and divine of a vow, a promise, a request, a moment in time, a life event, a miraculous healing, or even a more general affirming of the order of the world. Ex-votos are the material reminder of an ephemeral action; objects which are designed to commemorate. But, in this role, they are also far from objective. Each is deeply imbued with the emotions, memories, experiences, sensory knowledge, that was associated with their dedication and, let us not forget, their subsequent viewing by others. Their multiple authenticities lie embedded somewhere within this complex nexus of subjective meanings. Maybe thinking about how votives themselves might be agents of both memory- and meaning-making and, as such, objects caught up in the process of authenticating experiences, might enable us to think differently about how we interpret them.

Memory, of course, is especially pertinent to the study or understanding of ex-votos. A votive, after all, was intended primarily to serve as a mnemonic device, a reminder to both mortal and divine of a vow, a promise, a request, a moment in time, a life event, a miraculous healing, or even a more general affirming of the order of the world. Ex-votos are the material reminder of an ephemeral action; objects which are designed to commemorate. But, in this role, they are also far from objective. Each is deeply imbued with the emotions, memories, experiences, sensory knowledge, that was associated with their dedication and, let us not forget, their subsequent viewing by others. Their multiple authenticities lie embedded somewhere within this complex nexus of subjective meanings. Maybe thinking about how votives themselves might be agents of both memory- and meaning-making and, as such, objects caught up in the process of authenticating experiences, might enable us to think differently about how we interpret them.

Objects and Remembering reminded me about the extent to which humans need objects. We need them to negotiate our emotions, our senses, our experiences and our memories. We need them as a means of communication. They allow us to understand our personal experiences, to ground our memories in something tangible, to create new memories and forget others, to give meaning to what we do, but they also allow us to make connections with others, to function as a community and to understand the emotions and lives of others. Even the absence of objects is important, drawing attention to ways of thinking and of being that are consequently out of the norm, providing another strategic means of creating meaning within the world. Votives are part of the subjective object landscape with which we are surrounded and through which we create meaning in the world. What is more, as a distinctive type of ‘memory object’ they might productively be brought into wider discussions of meaning-making and materiality.

So, I for one have a lot to think about (and a lot of references to chase up!) but, if nothing else, the conference showed me how profitable it can be to step outside our traditional disciplinary boundaries and to question the authenticity of our own understandings of what happens when humans touch, hold, see, manipulate or otherwise interact with material objects.

Fascinating stuff, E-J, and I wish I’d been at the conference too! For me, the idea that votives function as divine memory aids is particularly intriguing because it implies that gods can forget, or at least that they can only attend to a limited number of things at any one time. I’ve heard later Catholic votives described as ‘pro memoria’, which again suggests a ‘forgetful god’ – and perhaps has implications for the idea of divine omniscience? Certainly it suggests that gods need objects too – just like humans!

This is such an interesting topic, and it would be good to collect some sources that connect votives with memory/remembering. E.g. Van Straten [in Faith, Hope and Worship] draws attention to an inscription on a votive image of a priestess of Aphrodite from Argos (third century BC) which translates: ‘Blessed Kypris, look after Timanthis; with/on account of a prayer for her sake Timanthes [= her dad] sets up this image so that later too, of goddess, when this sanctuary on the promontory is visited, a thought be given to this servant of yours.’

Jess – I think you are absolutely right. I suppose I’ve always rather just taken for granted that they are ‘memory’ objects, without thinking about quite what the implications are. I think it also depends upon who they are aimed at – are they memory aids designed to prompt the divine into remembering your request (and remembering to actually respond to it – a material ‘to do list’?!), or for the gods to remember the fact that you did thank them for their assistance once so can be relied upon in the future should there be cause for another request? Are they memory aids designed to commemorate in some way the moment of either the initial vow, or the outcome of it, and to make it tangible? Might this, in turn, remind both gods and humans that they share a bond? Are they designed to remind the wider community of their responsibilities to the gods, to act as a way of signalling that this is how things have always been done and should continue to be done? Are they – as we often think – designed to ‘remind’ new visitors to a sanctuary of the power of the divine? (I’m thinking here of inscriptions which recount miraculous healing and, in the process, suggest that the same could happen to you too). And then there is the issue of whether this ‘memorialising’ lends some sort of ‘authenticity’ to the whole process by making it more tangible. Lots to be thought about there and of course there is no reason why they can’t sometimes be all, or none of these things!

Collecting together some sources is a great idea because they might shed light on how people thought about the remembering aspects of votive cult. Equally, it would be interesting to know how this manifests itself today and whether memory plays a role and, if so, what that might be, in ongoing votive ritual.

Reblogged this on Objects and Remembering and commented:

This is a great overview of the conference by Emma-Jayne Graham, who talked to us about votives – terracotta babies given to the Gods

Thanks for a very thought provoking post – it sounds like a wonderful conference and the interdisciplinary approach sounds like it was exceedingly positive and fruitful. I’m starting a PhD soon in Museum Studies at the University of Leicester focusing on photograaphs in British museum collections of Maori, the indigenous people of New Zealand. I’m particularly interesting in the materiality of photos as objects, their use by Maori and their historical and contemporary use in museums. I think that many of the ideas discussed in terms of votives could equally apply to photographs. It was really inspiring to read about this coming at it from a different angle – that always helps to stimulate new ideas and consolidate one’s own thoughts.

I am really pleased that you found it thought provoking Natasha! Your upcoming project sounds really interesting and I wish you all the best getting started with it. Photos, I think, are interesting objects because they seem to encourage us to focus on just their visual elements and what they show, but they are (at least until the advent of digital photography anyway), also physical objects with other properties that we can interact with. I look forward to seeing what you come up with on the subject of the Maori photos!

Indeed the physicality of photos as objects is a really interesting one, which engages many of the senses, not just sight. I’m really looking forward to getting into my research. The double aspect of looking at photos showing Maori with their material culture is also something that I’m keen to look at – this could be looked at objects within an photographic object, if that makes sense. Many thanks for the good wishes 🙂

A very thoughtful piece. I’ve been engaged with this area for many years. My documentary film, Objects and Memory (www.objectsandmemory.org), shown nationally on US public television, started in the aftermath of 9/11, when I saw curators saving things from that event. It soon became clear that we all – as individuals and as societies – have things that may not mean anything to someone else, but for us are irreplaceable. Since the release of the film I’ve been speaking at universities and museums about the many issues surrounding how we navigate through a material world by imbuing otherwise ordinary things with meaning. You raise the issue of authenticity; why does it matter, as it does so much, that we are in the presence of the “real thing”? As you point out, authenticity resides in our belief about the object and its ability to connect us.