(or did ancient anatomical votives actually work?)

Votive offerings in the form of models of body parts are known from sacred sites across the ancient world. The common assumption is that many were linked to requests for divine intervention in instances of disease, illness, injury and other health conditions. Arguments can be made for alternative interpretations (my own view is that we should consider them as more complex multivalent objects) but let’s put that aside for the moment and focus on the dominant idea that, in the first instance at least, most were connected with health.

One question I often get asked, and one that I regularly ask myself, is did they work? Do the thousands of anatomical votives and related offerings (inscriptions, relief plaques etc.) from across the Mediterranean each attest to an occasion on which a petitioner was successfully cured of an ailment by the intervention of a divine figure? Similarly, if they didn’t always work then why did people keep making these offerings?

L0058489 Votive offering in the shape of a bladder, Roman, 200 BCE-20 Credit: Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Objects like this were left at healing sanctuaries and other religious sites as offerings to gods such as Asklepios, the Greco-Roman god of medicine. It was intended either to indicate the part of the body that needed help or as thanks for a cure. Made from bronze or terracotta, as in this case, a large range of different votive body parts were made and offered up in their thousands. Although it originated in earlier cultures, this practice became very popular in Roman Italy particularly between the 400s and 100s BCE. maker: Unknown maker Place made: Roman Republic and Empire made: 200 BCE – 200 CE Published: – Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

L0058429 Terracotta votive offering of a left thumb, Roman, 100 BCE-3 Credit: Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Objects like this thumb were left at healing sanctuaries and other religious sites as offerings to gods such as Asklepios, the Greco-Roman god of medicine. It was intended either to indicate the part of the body that needed help or as thanks for a cure. Made from bronze or terracotta, as in this case, a large range of different votive body parts were made and offered up in their thousands. Although it originated in earlier cultures, this practice became very popular in Roman Italy particularly between the 400s and 100s BCE. Perhaps this donor left the thumb because his or hers was broken or sore? maker: Unknown maker Place made: Roman Republic and Empire made: 100 BCE – 300 CE Published: – Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

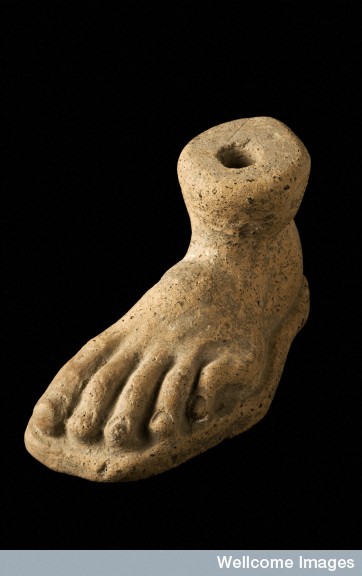

L0058428 Votive left foot, Roman, 200 BCE-200 CE Credit: Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Votive offerings are representations of afflicted body parts presented to a god, either in the hope of a cure or as thanks for one. This terracotta object may show the condition club foot, where the foot has not developed properly and causes difficulty when walking. maker: Unknown maker Place made: Roman Republic and Empire made: 200 BCE – 200 CE Published: – Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The answer may depend upon whether we think that anatomical votives were left at sacred sites as part of the initial request – to seal the deal, guide the attention of the deity to the specifics of the request, perhaps even jog their memory – or at a later stage, making them true ex-votos designed to give thanks and to commemorate a successful outcome. Either way, it is difficult to imagine that all petitioners left a sanctuary free of whatever ailment, injury, disease or illness had brought them there. Without straying too far into the dangerous waters surrounding retrospective diagnosis, it can be surmised that at least some of them would have been considerably impaired or suffering great pain (Graham, forthcoming), and we need only look at the so-called ‘miracle tales’ (iamata) from sites such as Epidaurus (Greece) to learn quite how debilitating some of the conditions that prompted people to seek divine intervention might be. On the other hand, some conditions might have cleared up on their own, or responded to supplementary forms of treatment administered by doctors or other healing specialists. If a visit to a healing sanctuary and/or a vow had been made in conjunction with these remedies an apparently spontaneous cure might well be explained in terms of successful divine intervention.

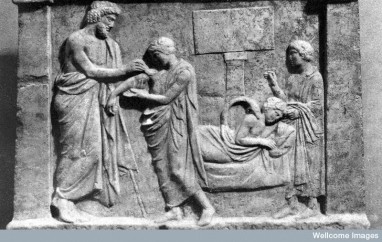

L0007389EA Relief in the form of a shrine, an offering from Archinos to Amphiaraos. First half of the 4th century BC. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images.

Equally, it may not even have mattered what the realities of the ‘success rate’ of each sanctuary or deity were (there were no NHS performance statistics to be collected in those days!). The mere presence of votive offerings testified to the potential healing powers of the relevant deity, intimating that these powers had intervened successfully to cure the bodies of other pilgrims. The accumulation of these objects in sacred places implied through their sheer numbers that divine treatment was a very real possibility. The iamata of the great Asclepieia of the eastern Mediterranean also spoke directly of the curative powers of the god.

“Nicanor, a lame man. While he was sitting wide-awake [in the sanctuary], a boy snatched his crutch from him and ran away. But Nicanor got up, pursued him, and so became well” (IG 4.1.121-22: Stele 1.16).

We might be suspicious of the extent to which these reflect real events or were a creative form of advertising on the part of cult officials but, together with other offerings and the presence of pilgrims with bodies at varying stages of the healing process, they suggested that if you behaved appropriately Asclepius was at least capable of bestowing a cure. The belief that vows could work was evidently important.

So far I have used the terms ‘cure’ and ‘healing’ interchangeably but we may want to think more critically about exactly what we mean when we ask whether ancient anatomical votives worked to ‘cure’ or to ‘heal’ petitioners. These terms can actually imply very different things, as anthropologists Andrew Strathern and Pamela J. Stewart (1999; 2008, p. 67) have pointed out:

“curing – the treatment of a specific isolatable disease syndrome – can usefully be distinguished from healing – the treatment of the person and their social relations as a means of dealing with the experience of illness and its resolution in recovery or otherwise” (emphasis added).

A quick internet search reveals that this distinction is employed across the medical and psychological sciences but, as far as I am aware, Strathern and Stewart’s study has not been integrated into work on ancient healing cult, nor have issues of curing vs. healing been explored in this context (although please do tell me if you know otherwise!). Reading even just a little about it has made me think in new ways about the efficacy of anatomical votives and how distinguishing between curing and healing might allow us to explore ancient understandings of health and the function of votive cult from different angles.

So, did an ancient votive petitioner actually expect what we, in the modern world, would think of as a complete cure – a total reversal of their symptoms, the removal of a debilitating condition, disease or tumour, the disappearance of an infected wound – or did they understand the act of seeking divine help as part of a more broadly defined healing process? Were cult activities a ‘means of dealing with the experience of illness’? That is, were they a way of making sense of why you were suffering, of treating the whole person, of making it easier to cope with your symptoms, rather than removing the specific ailment itself? If so, how might this be achieved? Communicating with the gods through mutual exchanges and ritual was a fundamental part of maintaining the security and stability of life in the ancient world. It must have made sense for people to consider their own personal health and well-being as one of the things that the gods could choose to influence and, as a consequence, it would be similarly reasonable to connect any ill health or misfortune with an imbalance in that relationship or dissatisfaction on the part of the divine. After all, in some cases illness was thought to be divinely inspired, a form of divine punishment that might result from improper behaviour deemed offensive to the gods, including, perhaps, inattention to their needs and a lapse in the performance of certain acts of worship. As Meredith McGuire (1990, p. 285) has observed, “since our important social relationships, our very sense of who we are, are intimately connected with our bodies and their routine functioning, being ill is disruptive and disordering.” The act of making a prayer, a vow or an offering, of seeking to ensure that the relationship between yourself and the divine was as it should be and that ‘all was well with the world’ may have been key to ensuring that ‘all was well’ with your body, even if you continued to experience pain or other symptoms. Offering a votive might, in other words, address the holistic experience and expectations surrounding illness and its causes, as much as it was ever expected to make it go away completely.

So, did an ancient votive petitioner actually expect what we, in the modern world, would think of as a complete cure – a total reversal of their symptoms, the removal of a debilitating condition, disease or tumour, the disappearance of an infected wound – or did they understand the act of seeking divine help as part of a more broadly defined healing process? Were cult activities a ‘means of dealing with the experience of illness’? That is, were they a way of making sense of why you were suffering, of treating the whole person, of making it easier to cope with your symptoms, rather than removing the specific ailment itself? If so, how might this be achieved? Communicating with the gods through mutual exchanges and ritual was a fundamental part of maintaining the security and stability of life in the ancient world. It must have made sense for people to consider their own personal health and well-being as one of the things that the gods could choose to influence and, as a consequence, it would be similarly reasonable to connect any ill health or misfortune with an imbalance in that relationship or dissatisfaction on the part of the divine. After all, in some cases illness was thought to be divinely inspired, a form of divine punishment that might result from improper behaviour deemed offensive to the gods, including, perhaps, inattention to their needs and a lapse in the performance of certain acts of worship. As Meredith McGuire (1990, p. 285) has observed, “since our important social relationships, our very sense of who we are, are intimately connected with our bodies and their routine functioning, being ill is disruptive and disordering.” The act of making a prayer, a vow or an offering, of seeking to ensure that the relationship between yourself and the divine was as it should be and that ‘all was well with the world’ may have been key to ensuring that ‘all was well’ with your body, even if you continued to experience pain or other symptoms. Offering a votive might, in other words, address the holistic experience and expectations surrounding illness and its causes, as much as it was ever expected to make it go away completely.

A votive torso: opening up the whole person to the intervention of the gods? L0058445 Roman, 200 BCE-200 CE Credit: Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images

As Strathern and Stewart (2008, p. 67) note, ‘curing, narrowly conceived, may be said to separate mind and body, whereas healing can be said to unite them.’ Anatomical votives by their very nature compel us to focus on the body and its constituent parts, but maybe some were intended to refer to a more general sense of physical health and well-being, an opening up or sharing of the body and its essence with the divine. As a consequence we might consider re-examining the emphasis that we place on the choice of body parts dedicated and the role of these material objects as direct signifiers of a person’s state of health.

Perhaps too we could think about revising prevailing ideas about how ancient people conceived of illness, impairment and health. I suspect that in many instances the lines that we as scholars can draw so easily between categories of ‘healing’ and ‘curing’ were blurred and it may be inappropriate to try to apply these labels too strictly. Nevertheless, for me at least, they have made me think more critically about exactly what anatomical votive offerings associated with health aimed to do and what the expected outcomes were. In many cases, the sense of well-being resulting from communicating directly with the divine realm, sharing that experience in a communal setting with other pilgrims and petitioners and knowing that others have done the same before you perhaps resulted in a sort of healing of a person’s sense of self and bodily security which meant that even if no direct cure was forthcoming votive cult really could be said to have ‘worked’ to restore unbalanced bodies.

E-J Graham

References

Graham, E-J. Forthcoming. Mobility impairment in the sanctuaries of early Roman Italy. In C. Laes (ed.). Disabilities in Antiquity. London and New York, Routledge.

McGuire, M.B. 1990. Religion and the body: rematerializing the human body in the social sciences of religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29(3), pp. 283-96.

Strathern, A. and Stewart, P.J. 1999. Curing and healing: medical anthropology in global perspective. Carolina Academic Press.

Strathern, A. and Stewart, P.J. 2008. Embodiment theory in performance and performativity. Journal of Ritual Studies 22(1), pp. 67-71.

Pingback: The Go Between, by Tabitha Moses | The Votives Project

Pingback: Votive visions of the body | The Votives Project

Pingback: The Ancient Greek Temple Why So Many Limbs Of the Sculpture? – EEKEE

Pingback: Research point: Unusual Materials & Collections – Understanding Painting Media: Alison512480

Made me think of Lourdes.